Sunday 2 October 2016

Tuesday 16 September 2014

Monday 19 May 2014

Monday 22 April 2013

click farewell

How come, you might ask, that a word spelled with -c- comes to be pronounced with an l? Why this gross discrepancy between spelling and sound, orthography and pronunciation?

Blame the 1989 Kiel Convention of the IPA, which replaced the click symbols then in use, ʇ ʗ ʖ, by the current ǀ ǃ ǁ.

Because the second syllable of this word is pronounced in Zulu with a voiceless dental click. Unfortunately in some fonts the currently official IPA symbol for this sound looks indistinguishable from a lower-case L.

For further discussion, together with a number of sensible readers' comments, see my blog for 9 Sep 2009.

_ _ _

…In fact over recent months I have increasingly been feeling that in this blog I have by now already said everything of interest that I want to say. And if I have nothing new to say, then the best plan is to stop talking.

So I am now discontinuing my blog.

Thank you, all those readers who have stayed with me over the seven years that I have been writing it. If you still need a regular fix, there are archives stretching back to 2006 for you to rummage through.

Goodbye, au revoir, tschüss, hwyl, cześć, tot ziens, до свидания, さようなら, ĝis!

ˌðæts \ɪt

Friday 19 April 2013

Breughel

We can’t agree on how to spell the name of the famous Dutch/Flemish painter(s): were Pieter B. the Elder and his relatives Breughel, Brueghel, Breugel or Bruegel?

As is often the case with foreign names in English, we’re not entirely sure how to pronounce them, either.

In Dutch this name is pronounced ˈbrøːɣəl (subject to the usual regional variationː possible diphthonging of the stressed vowel and devoicing of the velar, not to mention the variability in the second consonant), which is what you would expect for a spelling with eu. In turn, you would expect foreign-language ø(ː) to map onto nonrhotic English NURSE, as happens with French deux dø mapped onto BrE dɜː or German Goethe ˈɡøːtə onto BrE ˈɡɜːtə.

Yet on the whole we call the painter not ˈbrɜːɡl̩ but ˈbrɔɪɡl̩. Why?

I can only suppose that our usual pronunciation is based on the spelling with eu interpreted according to the reading rules of German. If Deutsch is English dɔɪtʃ and Freud is frɔɪd, then Breug(h)el must be ˈbrɔɪɡl̩.

For the same reason, even though Wikipedia prefers the spelling Bruegel (which would prompt us towards a pronunciation ˈbruːɡl̩), most of us, I suspect, tend to spell the name with eu.

Wednesday 17 April 2013

estuariality

I had a phone call a few days ago from someone trying to get in touch with David Rosewarne. The caller thought I might have his contact details. I was unable to help, since as far as I remember I have only met Rosewarne once, and that briefly; the last I heard of him was that he was working in Malaysia, but I do not know where he might be now.

David Rosewarne’s great claim to fame is that in October 1984 he coined the expression “Estuary English”, in an article published in the Times Educational Supplement.

In doing so he gave expression to the widespread perception that Daniel Jones-style RP was gradually losing its status as the unquestioned standard accent of educated English people. Or, putting it a different way, that RP was changing by absorbing various sound changes that previously had been restricted to Cockney or other non-prestigious varieties.

Two years earlier, in my Accents of English, I had written

Throughout [London], the working-class accent is one which shares the general characteristics of Cockney. We shall refer to this accent as popular London. […] Middle-class speakers typically use an accent closer to RP than popular London. But the vast majority of such speakers nevertheless have some regional characteristics [emphasis added]. This kind of accent might be referred to as London (or, more generally, south-eastern) Regional Standard.

I added the warning

It must be remembered that labels such as ‘popular London’, ‘London Regional Standard’ do not refer to entities we can reify but to areas along a continuum stretching from broad Cockney (itself something of an abstraction) to RP.

So Rosewarne’s observations in a sense contained nothing new. He muddied the waters unhelpfully by referring to details of vocabulary and grammar (which have nothing to do with “a new variety of pronunciation”). But the name he coined, Estuary English, was taken up quite widely, gaining resonance eventually not only with journalists but also with the general public, to such an extent that we can now expect to be readily understood if we describe someone’s speech as “estuarial”.

The estuary Rosewarne was thinking of was of course the Thames estuary, which in a geographical sense might be interpreted as extending from Teddington near Kingston upon Thames (the point where the river becomes tidal) down to Southend-on-Sea (where the Thames enters the North Sea). Rosewarne’s original article says “the heartland of this variety lies by the banks of the Thames and its estuary, but it seems to be the most influential accent in the south-east of England”; though later writers, particularly Coggle in his Do you speak Estuary? (1993) implied that it covered the entire southeast of the country. It was left to my colleague Joanna Przedlacka to demonstrate that it did no such thing (see her 2002 book Estuary English? and this summary). Przedlacka demolished the claim that EE was a single entity sweeping the southeast. Rather, we have various sound changes emanating from working-class London speech, each spreading independently.

Rosewarne’s suggestion that EE “may become the RP of the future” led to credulous excitement in the EFL world, particularly in central Europe and South America.

It was in response to media and academic interest in the topic that in 1998 I set up a website “to bring together as many documents as possible that relate to Estuary English, as a convenient resource for the many interested enquirers.”

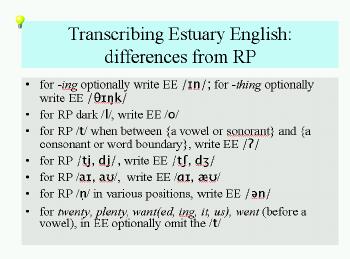

One thing I did myself was to consider how we might agree on a phonetic transcription scheme, which would be needed for pedagogical purposes if we seriously wanted to teach this putative new accent. See this article. But no one followed this up by criticizing my proposals or suggesting anything better.

All the excitement gradually died down. I last had cause to update the website in 2007. By the time I retired, in 2006, this was my one-page summary of the issue. EFL teachers, meanwhile, mostly know that we just need to update our pedagogical model of RP in the minor ways outlined in LPD.

Monday 15 April 2013

London place names

Londonist, a website “about London and everything that happens in it” offers a page of advice on London place names.

Some of the advice is a little surprising.

These names are normally ˈɔːldwɪtʃ, ˈbʌrə, kəˈdʌɡən, ˈtʃɪzɪk, ˈklæpəm, ˈdeʔfəd, ˈdʌlɪdʒ. RP usually distinguishes ˈɔːl from əʊl and ɒl (so that Paul ≠ pole ≠ Poll(y)), and Aldwych has ɔːl or possibly ɒl, but not əʊl. Of course many speakers have the GOAT allophone ɒʊ when dark l follows, as here; and Londoners tend to vocalize dark l, making cold kɒod; but I had thought that most would not merge the result with the ɔːo of l-vocalized called. Hence I am surprised to see Aldwich explained as “old witch”; though I suppose “all’d witch” or “auld witch” would be orthographically awkward. (Anyhow, the main point is that -wych stands for wɪtʃ, not wɪk.)

With Clapham, the basic ˈklæpəm can of course be reduced to ˈklæʔm̩ by the regular processes of syllabic consonant formation and glottalling.

The final consonant in Dulwich is, in my judgment, more often dʒ than tʃ, though both are possible; it’s odd that the anonymous author should prescribe the voiceless affricate in Dulwich but the voiced one in Greenwich and Woolwich, where the same hesitation between the two possibilities for -ch applies.

That’s ˈhəʊbən, ˈhɒmətən, ˈaɪzəlwɜːθ, with the usual syllabic-consonant options, plus possible glottalling in ˈhɒməʔn̩ and weakening in ˈaɪzl̩wəθ (or, of course, a more London-y ˈɑɪzowəf). Initial h is just as likely to be dropped/retained in Holborn as in Homerton.

So, ˈplɑːstəʊ (though I’ll allow people from the north of England and the Americans to say ˈplæstəʊ if they prefer), ˈrɒðəhaɪð, ˈraɪslɪp,ˈsʌðək, ˈstretəm, ˌθeɪdənˈbɔɪz, ˈtɒtənəm, ˈwɒpɪŋ. Regular optional processes generate the variants ˈrɒvəhaɪv, ˈstreʔm̩ and ˈtɒʔnəm; there is also an archaic variant ˈredrɪf (Redriff) for Rotherhithe; and if you drop the h in the usual form you'll get an internal linking r, ˈrɒvəraɪv. The Cockney tube train driver on my AofE recording pronounces his part of London, Wapping, as ˈwɒpʔɪn.